The following article is a wonderful tribute to Moses Van Campen appearing in Hazard's Register of Pennsylvania in 1833. Visit the Timeline, Sketches, and In Honor pages for additional articles which collectively tell the life story of Moses Van Campen.

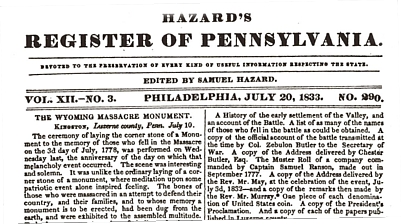

HAZARD’S REGISTER OF PENNSYLVANIA

Devoted to the Preservation of Every Kind of Useful Information Respecting the State.

Edited by Samuel Hazard.

Vol. XII.-No. 3. No. 290. Philadelphia, July 20, 1833.

From the Young Man’s Advocate.

MAJ. MOSES VAN CAMPEN.

We take up the pen to notice a few prominent scenes in the life of this revolutionary patriot. We shall make no attempt at a biographical sketch; our purpose is barely to give publicity to the acts which marked his early military career in the war of the revolution.

Cover of "Hazard's Register of Pennsylvania. Vol. XII.-No. 3. No. 290. Philadelphia, July 20, 1833.That oblivion should envelope in its dusky folds the important services of many of our veteran soldiers is a reproach upon the national honor; and, as long as the meed of gratitude is withheld, a stain rests on the page which tells the moving history of this proud republic. The grave has closed on worth and, genius – that where and how would unfold a story of national wrong and injustice over which posterity will drop the unbidden tear. In the wilds of the western mountains, forgotten and neglected, the high-born and gallant patriot, Arthur St. Clair, closed his earthly pilgrimage.Justice, long delayed, came with its award in time to behold the closing ritual from the hand of strangers. How many of that glorious band, who toiled for the liberties of their country, have been left in ignominious silence, to slumber out the remnant of their days, and pass from among us unhonored and forgotten, cannot now be told. Tardy gratitude comes with the sting of death, and had better be withheld than bestowed. The neglect of this age will receive the just censure of the next, and when posterity shall hold in veneration the names of the fathers of our country, the bitter curse of national ingratitude will be irrevocably fixed upon that period where we could least wish to behold the inglorious stigma.

Cover of "Hazard's Register of Pennsylvania. Vol. XII.-No. 3. No. 290. Philadelphia, July 20, 1833.That oblivion should envelope in its dusky folds the important services of many of our veteran soldiers is a reproach upon the national honor; and, as long as the meed of gratitude is withheld, a stain rests on the page which tells the moving history of this proud republic. The grave has closed on worth and, genius – that where and how would unfold a story of national wrong and injustice over which posterity will drop the unbidden tear. In the wilds of the western mountains, forgotten and neglected, the high-born and gallant patriot, Arthur St. Clair, closed his earthly pilgrimage.Justice, long delayed, came with its award in time to behold the closing ritual from the hand of strangers. How many of that glorious band, who toiled for the liberties of their country, have been left in ignominious silence, to slumber out the remnant of their days, and pass from among us unhonored and forgotten, cannot now be told. Tardy gratitude comes with the sting of death, and had better be withheld than bestowed. The neglect of this age will receive the just censure of the next, and when posterity shall hold in veneration the names of the fathers of our country, the bitter curse of national ingratitude will be irrevocably fixed upon that period where we could least wish to behold the inglorious stigma.

The war of the revolution broke out in the year 1775. Great Britain sent her ships and armies to coerce her American subjects into an humble submission to laws unjust and oppressive in the extreme. The battles of Lexington and Banker Hill soon taught his Majesty George III that a manly resistance would be made, and that the revolted colonies would prefer death before submission.All the western posts on the waters of the great lakes, were in the possession of the British. Agents were sent by the crown to all the Indian tribes, from the province or Maine to the state of Georgia, with gold to purchase their friendship and allegiance; and without the exception of single tribe, the whole savage population became allies to the British government. This band of ruthless foes was stretched like a chain around our western frontiers. On the sea-board the British troops were to be opposed, and on the western borders, the united force of British tories, and Indians.

The subject of this notice was then a citizen of Northumberland county, Pa.After the declaration of Independence, in the year 1776, in the 18th year of his age, he renounced his allegiance to the King of Great Britain, and took up arms in defense of his country. Having served as a volunteer until August, 1777, he then joined the regiment commanded by Col John Kelly, stationed at Big Island, and Bald Eagle creek, on the west branch of the Susquehanna. He served in this regiment three months. It was during this period that the Indians were roving through the sparsely settled country, in small detachments, spreading havoc and death to a fearful extent. There remained no longer any safety for the inhabitants, as the fires of the savages were nightly lights from the dwellings of their murdered victims.

The same year, Van Campen intercepted a small party of Indians, and, in the conflict that ensued, he succeeded in killing five. The chief and party ran. In Spring of 1779, a number of companies of boatmen were raised to man the boats built by Government to convey the provisions for Sullivan's army, from sundry place of deposit on the Susquehanna river, to Wilkes-Barre, and from thence to Tioga Point. Van Campen was appointed Quarter Master of that department, and superintended the conveyance of the provisions to Tioga Point by water. While the army was lying at Tioga point, waiting for General James Clinton to arrive with his brigade, at the request of Gen. Sullivan, he reconnoitered the Indian camp at Chemung. The next night, Van Campen went with a detachment, and fought the Indians, at a place called Hoqback Hill, and routed from their ambuscade, with some loss of killed and wounded.

In March, 1780, a party of Indians reached the frontiers in the neighborhood of his father's farm, and as Sullivan, in 1779, had destroyed their towns and villages, it was thought they would not venture upon their accustomed deeds of violence. In the hope that the frontiers would have some rest, and lulled into a fatal security from the shy movements of this band of savage warriors, many returned to their homes, and ventured to engage in their ordinary occupations. Van Campen went with his father to his Farm, and assisted in erecting a shanty for lodging. On the morning of the 29th of March, they were surprised by a party of ten Indians. His father and brother were inhumanly killed, scalped, and thrown on the fire, and himself taken prisoner.

Van Campen was pinioned and the party their march. Two other prisoners were taken in the course of the next day. Their route over the mountain was very difficult, and in many places the snow was deep. They came to the north branch of the Susquehanna, at little Tunkhannock creek where the Indians had moored their canoes after descending the river. When they had crossed over to the east side, the canoes were propelled into the middle of the stream and set adrift. The party then proceeded along the bank of the river toward its source. On the way to Whilusink, Van Campen improved an opportunity which the unwonted carelessness of the Indians offered, in suggesting to his companions in captivity a plan of escape, only, however, to be effected in the total massacre of the Indian party.

The motive for such a daring attempt was indeed a powerful one, for he well knew their fate, being the first prisoners taken after Sullivan's campaign. Van Campen was well aware, that under these unfavorable auspices, they would, after a parade in savage triumph through the Indian villages, suffer every torture that dispositions wild, uncontrolled, and revengeful, could suggest, and finally grace a burning pile. He reasoned under these convictions, that they had now an inch of ground to fight on, and if they did not succeed, the alternative was to sell their lives as dearly as possible. If another day should close upon them in captivity, and it would soon wing its course, hope would grow faint, and per chance the taunt the triumphs, and the lingering death, would be meted out in all its horrors, while every effort at manly resistance would be palsied. His fellow prisoners agreed to join in the attempt. The natural vigilance of the Indians returned, and it was well for the prisoners that they were far from the place of destination.

On the fourth day of their captivity, a few moments offered for consultation on the mode of attack. As theIndians had on former nights laid five on each side of the fire, the prisoners bound and placed between them, Van Campen's plan was to procure a knife, and at an hour when they were sound in sleep, cut off their bands, disarm the savages of their guns and tomahawks, and the three prisoners with each a tomahawk, come to close work at once. This plan was objected to by the other two. All agreed in the necessity of disarming. The objectors to Van Campen's mode, thought it best for one of the party to fire upon the Indians, on one side of the fire, while the remaining two were engaged in the work of death on the other. Van Campen was decidedly opposed to this proposition, as the moment a shot was fired, the alarm would be given, and it would then involve the issue in a dreadful uncertainty. They were obstinate, and as there remained no alternative, he submitted, and they pledged themselves one to the other to fight unto the death in the proposed conflict, rather than remain long in captivity, with a cruel death in the prospect.

On the night of the second of April, about 12 o'clock, the prisoners concluded that all the Indians were sound in sleep. Van Campen had previously procured a knife. They rose, cut themselves loose, and immediately removed all the arms. It was a moment of the most thrilling interest; five brawny savages were stretched at length on either side of the fire. The faint light emitted from the burning brands, scarcely threw back the shadows of night from the sleeping forms. Their outlines, however, were full and fair to the eye accustomed to watching through the heavy hours of a night in the wilderness. At that moment two of the Indians awoke, and discovered the situation of the captives. Van Campen and one of the men were on one side of the fire – his partner proved the coward. Not a moment was to be lost; in an instant the two that were rising fell before his tomahawk, and sunk into the arms of death.He despatched the third one, when the shot was made on the opposite side of the fire. The alarm was then general. Three were mortally wounded from the shots – four still remained.

Van Campen's Encounter with Mohawk - Illlustration by A.R. Dodd from Sketches of Border Adventures in the Life and Times of Major Moses Van Campen, by J.N. Hubbard and J.S. Minard, 2nd Edition, 1893.Van Campen gave one a severe wound as he was on the jump. The stroke was aimed at his head, but sunk into his shoulder. He fell, and unfortunately as Van Campen was on the leap after the savage, his foot slipped, and he fell by his side. They grappled together, each exerting his utmost power to prevent the use of the knife and tomahawk. After a short and severe struggle, they mutually relax their hold, which was no sooner done than the Indian regained his feet and run. The victory was complete, only one of the ten Indians, who had laid down to repose in confidence and security that evening, ever reached their villages or Fort Niagara.

Van Campen's Encounter with Mohawk - Illlustration by A.R. Dodd from Sketches of Border Adventures in the Life and Times of Major Moses Van Campen, by J.N. Hubbard and J.S. Minard, 2nd Edition, 1893.Van Campen gave one a severe wound as he was on the jump. The stroke was aimed at his head, but sunk into his shoulder. He fell, and unfortunately as Van Campen was on the leap after the savage, his foot slipped, and he fell by his side. They grappled together, each exerting his utmost power to prevent the use of the knife and tomahawk. After a short and severe struggle, they mutually relax their hold, which was no sooner done than the Indian regained his feet and run. The victory was complete, only one of the ten Indians, who had laid down to repose in confidence and security that evening, ever reached their villages or Fort Niagara.

We would here observe, that common report says, many years after this conflict, the Indian who so narrowly escaped with his life called upon Major Van Campen at residence, where a mutual recognition took place. The subject of that eventful evening was talked over, when the Indian, after partaking of the hospitalities of the house, departed on apparently friendly terms.

On the 8th of April, Van Campen, was commissioned as a Lieutenant of Infantry, in the Pennsylvania line, the remaining part of the year was spent in recruiting a company, when organized, they mustered 110 men, and were detached from the frontier service. In the year 1781, it was reported that a large body of Indians lay on the Cinimihone river, west branch of the Susquehanna.Col. Samuel Hunter, who was then in command, selected Capt. Peter Grove, Capt. William Campbell, Lieutenants Grove, Creamer, and Van Campen, to act as spies in discovering the location of the Indian forces, to ascertain their size, watch their movements, and to make report by sending in one of their number. They marched in the month of August, but made no discovery. On their return one evening about sun setting, they discovered a smoke which they at once concluded must proceed from an Indian camp. The number could not be determined; at all events, it was settled in council to give them battle that night. They were dressed and painted in Indian style. Each had a good rifle, tomahawk, and a long rifle. It was a fine evening; all felt fit for action, and eager for the conflict. The appointed time came, and, with a silent and stealthy step, they reached the camp undiscovered. To their surprise, they found that the battle must be waged with about thirty Indian warriors. They kept their rank, and each man fought arm to arm; first used the tomahawk and knife, and then poured in their five shots – raised the warwhoop, and roused the whole party with a Ioss of four killed and several wounded. It was a roving party that had long been a terror to the frontier settlers; they had killed and scalped two or three families, and plundered every house they had visited.

In the spring 1782, Van Campen was sent with a party of 25 men, up the west branch of the Susquehanna river. On the morning of the 16th April, on Bald Eagle creek he met with 85 Indian warriors. A severe battle took place; 19 of his men were killed, himself and five taken prisoners. The day after the battle the Indians killed one of the prisoners for some trifling cause.

Van Campen and his fellow prisoners were marched through the Indian villages, some were adopted to make up the loss of those killed in the action. Van Campen passed through all their villages undiscovered; neither was it known that he had been a prisoner before, and only effected his escape by killing the party, until he had been delivered up to the British at Fort Niagara. As soon as his name was made known it became public among the Indians. They immediately demanded him of the British Officer, and offered a number of prisoners in exchange. The commander on the station sent forthwith an officer to examine him. He stated the facts to the officer concerning his killing the party of savages. The officer replied that his case was desperate. Van Campen observed that he considered himself a prisoner of war to the British; that he thought they possessed more honor than to deliver him up to the Indians to be burnt at the stake; and in case they did, they might depend upon retaliation in the life of one of their officers. The officer withdraw, but shortly returned and informed him that there remained no alternative for him to save his life, but to abandon the rebel cause and join the British standard. A farther inducement was offered that he should hold the same rank that he now possessed, in the British service. The answer of Van Campen was worthy the hero, and testified the heart of the patriot never quailed under the most trying circumstances. "No sir, no: my life belongs to my country; give the stake, the tomahawk, or the scalping knife, before I will dishonor the character of an American officer."

In a few days, Van Campen was sent down the lake to Montreal, and there put in close confinement, with about 40 American officers. In the month of September he was taken out of prison, with ten of the other officers, and sent to Quebec. From thence they were removed to the Isle of Orleans, on the St. Lawrence, 24 miles below the city. About the 1st of November they were put on board a British vessel, which sailed to New York, when he was exchanged, and immediately returned to the service of his country.

On the 16th of November, 1783, he was finally discharged from the army or the United States, after a perilous service of a little more than 7 years.

Major Van Campen is still living, [at Danville, Livingston Co.] in green old age, in possession of his faculties, and enjoying, in common with his countrymen, the fruits of our free institutions, which have sprung into life since he mingled in the revolutionary contest. He is respected for his patriotism and bravery, and beloved for the amiable qualities of his mind, by an extensive circle of friend. Benevolent in his disposition his life, since the revolution, has been spent, not in hoarding up wealth for self gratification, but In alleviating the distresses of the unfortunate, and extending the hand of charity to the wants of his fellow beings.

B. Wayne, N. Y. August 13.